the individual and the masses

- Ana Paula Arendt

- 20 de ago. de 2025

- 22 min de leitura

Atualizado: 23 de ago. de 2025

The Individual and the Masses

Ana Paula Arendt*

Where did we get this idea that large masses of people in the streets demanding any political ideas would be an authentic expression of democracy? We haven't asked ourselves very much this question recently.

We passively take it as a given that a large contingent of people would undoubtedly confer legitimacy and political strength on a movement or party. Journalists, authorities, and university researchers quickly compete to establish the number closest to reality, with their explanations—or lack thereof. The debate then revolves around the number of people, assuming as true the thesis that the more individuals, the greater the political strength.

However, when I open the old book "Psychology of the Masses" by the Austrian Sigmund Freud, I come across his study of the literature of the time, and this quote, a pearl of wisdom rescuing our common sense:

“Moreover, the mere fact that he [the individual] forms part of an organized crowd, a man descends several rungs in the ladder of civilization. Isolated, he may be a cultivated individual; in a crowd, he is a barbarian – that is, a creature acting by instinct. He possesses the spontaneity, the violence, the ferocity, and also the enthusiasm and heroism of primitive beings (…)”. Gustave le Bon, Psychologie des foules, 1895. (Gustave le Bon, Psychologie des foules, 1895.)

And also an excerpt from the German poet Schiller (1759-1805), a friend of Goethe:

“Every man, seen as an individual, is tolerably shrewd and sensible; see them in corpore (in a crowd), and you will instantly find a fool”.

Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, wrote about this subject between 1907 and 1920, therefore before the First World War and during the bloody conflict. He did not live to witness the height of N4zism and government based on mass control, as he died in 1939. But his writings deepened Le Bon's theory and included new variables to explain why people deprive themselves of logic and the ability to think, to follow a leader, becoming part of a crowd.

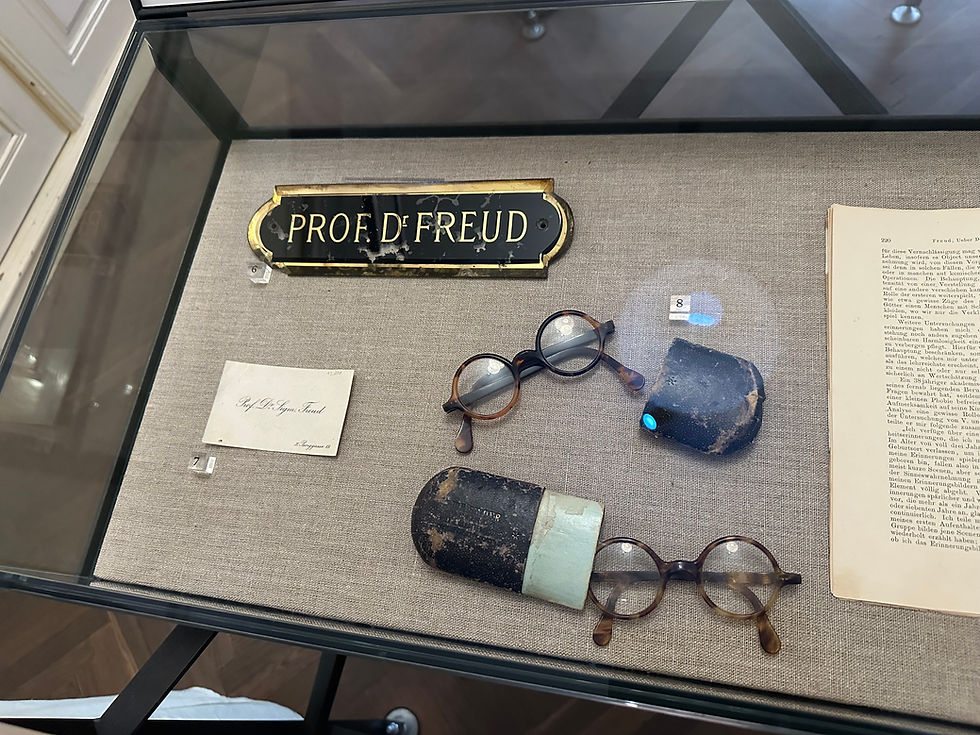

I found the old book "Mass Psychology and Other Writings" in Freud's own home in Vienna. I was researching exactly where the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations had been signed, at the Neue Hofburg. It's an instinct: it seems to me that whenever we face a problem, a violation, I find it advisable to return to the starting point where the agreements were made, to find the origin and the answer to our questions. Thus, since ancient times, we have evoked our ancestors—in this case, not our blood relatives, but those who preceded us—who created an order to try to overcome the difficulties of a chaotic reality. In this case, I was seeking the origin of our order to prevent wars of vast proportions and safeguard friendship between peoples. All very vast, it's true! But that's the life of a poet: dedicating oneself to these vast things. The library of the Neue Hofburg Palace was closed, sadly. No one knew where the Vienna Convention had been signed; although probably in the library, it was still there. And the conference hall is now a private space, occupied by the OSCE. There seems to be no memory... So, all that was left was to visit Freud's house.

Vienna is close to Belgrade; there was even a time when part of Serbia was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. To my surprise, Vienna was the destination my children spontaneously chose for their vacation, before I shared my idea with them. And there we were, enjoying the abundance of well-preserved museum collections, including Freud's house, now a museum.

I thought it interesting to learn a little more about the history of Austria. There, we received Dom Pedro I's wife, Empress Leopoldina. It was this woman who, while Dom Pedro I rode with his friends, signed Brazil's independence, following a session of the Council of State. Having sent a letter to her husband, only after her confirmation did he give the cry that became recorded in Brazilian history, on the banks of the Ipiranga River, consummating what had been prepared and signed by his wife. Dom Pedro I gave the order, but the political articulation was spearheaded, at the Court, by the intelligence of a Habsburg woman. Indeed, Schönbrunn Castle, the Habsburg seat, stands out among all those I've visited for its beauty and spaciousness.

But I had never realized, nor stopped to observe, before this, even though we study history books about how the rise of N4zism in Austria came about. How could a country that produced Mozart, Strauss, and Schubert, a place where Beethoven and Vivaldi chose to die, suddenly decide to follow Hitler and Mussolini? How could a country that bequeathed Hans Kelsen to the world, and that was home to a dynasty with a legendary civilizing tradition and a high cultural level, have been assimilated by a movement that preached the most complete barbarity? No one would have thought it possible that, due to its distinct cultural aspects and the calm, optimistic, and open temperament of its people, Austria could become a pantheon of a dictatorship and join the efforts to subjugate Europe and the world through extreme violence. However, they went through a period of dictatorial loss of control.

Image: Detail of the Belvedere Palace and the Parliamentarians' Club

Meanwhile, dictator Engelbert Dollfuss ruled Austria from 1932 to 1934 with all the trappings of a N4zi movement: he was an ally of Mussolini. He suppressed the socialist movement during the Austrian Civil War and banned the Austrian N4zi Party. He was assassinated as part of a failed coup attempt by N4zi agents in 1934. The assassins were convicted; and Mussolini attended his funeral and condemned the assassination attempt on Dollfuss, as he was antagonizing Hitler at the time. Dollfuss was succeeded by Kurt Schuschnigg, who maintained the authoritarian regime until the unification of Germany and Austria, Adolf Hitler's Anschluss, in 1938. It is during this period that the plot of the famous film "The Sound of Music" takes place, and when Bertold Brecht describes Dollfuss through one of the characters in his book The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui (1941).

I share with my readers the images demonstrating, in practice, what Le Bon and Freud were studying in those decades that preceded the transformation of politics into a mass phenomenon.

Panels from the Austrian History Museum, in the Neue Hofburg

In those critical decades, Kelsen was a mentor of democratic thought and constitutional courts, the so-called compromise democracy; but he was in favor of the Anschluss, the union between Germany and Austria. This was another mistake of his, in addition to elevating Carl Schmitt, as so many jurists do, to the stature of an intellectual, when he was a propagandist. The Jewish jurist failed to see that the integration of Germany and Austria would result in the integration of two radical far-right groups; he underestimated their purposes. It was from this union that the movement gained strength to project itself across the European continent and led to the inclusion of other leaders in a broader political coalition, such as Mussolini, and, later, the formation of the Axis.

Kelsen's legal idealism has survived the test of time because it proved more suitable for promoting a balance between diverse political forces and ensuring government stability.

This entire totalitarian phenomenon that darkened Europe, it is true, lasted a very short time: after World War II, the Anchluss was banned, and Austria returned to normal. Dictatorial regimes based on an extremist creed are extremely unstable: they need to continually feed on triumphs and victories to display the virility their leaders arrogate to themselves. But after World War II, the conurbation of two extremist and radical political movements with violent ideologies, Austria suffered great damage, like all of Europe, which saw itself destroyed.

The misfortune and joy of intellectuals and humanists, in general, is the faith in the superiority of the values they defend, and that good will always triumph in the end. Don't I believe so? Obviously, I believe so, but that doesn't stop me from seeing that Kelsen's idealism, like the letter sent by Pope Pius XI, the only one written in German, directly addressed to the people of those countries, Mit brennender Sorge, only served as a subtle reminder of the indignity of N4zi values. These efforts, based on moral superiority—whether correct or not—did nothing concretely to alleviate the burden of the invaded, harmed, and persecuted peoples. Could it have been different? So why wasn't it different?

But well before that, and perhaps capturing the collective unrest of those decades, Freud analyzed several characteristics attributed by Le Bon to the masses. I find it interesting that I was never introduced to this text of his, despite having graduated in Humanities. On the contrary: at university, I learned that Freud's work was categorized as pseudoscience, since his assertions could not be proven—they did not meet the demanding criterion of objectivity of the counterfactual, in Popper's formula.

So today I see this as perhaps the greatest stupidity I committed during my youth: readily assimilating an argument by its logic, discarding, by its form, something that might contribute to increasing the understanding of a problem.

Freud's office, inside his own apartment, at 19 Bergasse Street, Vienna.

I also remember there was a prejudice among the fashionable neo-institutionalist scholars of my time that Freud was a drug addict—indeed, he was addicted to cocaine. In fact, he thought cocaine could be a solution to morphine addiction. His best friend, a doctor and morphine addict, offered to be a guinea pig for this thesis; he ended up addicted to both morphine and cocaine and died. Freud, we learned during our visit to his home, kept a framed photo of this friend he lost on the small table next to his armchair.

We fell silent, lamenting with Freud his terrible idea, thinking of our best friends, of what we would do in his place; but admiring, nonetheless, the love he had for his friend and the discernment he had in retaining the memory of his failure every day.

I explained to my children what I know in general about his theses, as they seemed very interested and read all the panels, about Oedipus drives, totems, taboos... I explained that Freud argued that every child desires their mother and wants to kill their father to possess their mother. They were then laconic: they said, "Freud is a sick man." It was too much laugh seeing the repulsive expression in their faces. The museum is child-friendly and has board games, souvenirs with Freud's image, and the inscription "I love Mum”...

But the truth, delving deeper into the subject, is that, in the words of French psychoanalyst Madeleine Vermorel, Freud's work was not born of a scientific impulse, but is practically entirely based on Schiller's poetry. She explains that Freud elaborated on the relationship between mother and child "based on the poem 'Der Taucher' (The Diver), to evoke the dangers of the maternal body inhabited by monsters, citing the diver's ascent toward the 'rosy light' to justify why he avoided submerging himself in the maternal unconscious.”

Freud also allegedly used the poem "The Ring of Polycrates" as an illustration for one of his works, which I hope to read and translate for friends and readers. A very interesting story from Herodotus, about a Tyrian who threw his ring into the sea and found it again when he opened the fish that swallowed him; afterward, he was abandoned by his Egyptian ally and crucified by a Persian ally.

But what matters to us is that Goethe and Schiller are, for Freud, the prehistory of psychoanalysis, proposed as a discipline for the study of the human soul, an approach to a problem through attention to the other, listening, and affection. How could we explain the world, or see it satisfactorily, without taking into account poetry and attention to others, listening and affection? The encounter between the unconscious and language produces poetry; from this, the beauty of life is revealed. Anyone who lived without ever finding their own feelings in the words of a love poem would be incapable of celebrating the acts that underpin civilization. How could anyone understand the human world and themselves if they discarded the emotional dimension of events?

It is also undeniable that poetry is not a form of writing detached from time and collectivity. Polycrates' ring, one of Schiller's poems from 1797, used by Freud in his analysis of the 1919 book "The Sinister," has its roots in the account of Herodotus (History 3, 122-126), a poem I will translate in the next post. Just like Shakespeare's Macbeth and so many other images and content of symbolic value that he uses to analyze why people behave the way they do. It was all the rage, just as the Star Wars series reverberates in our time, the opera "The Ring of Polycrates," with Erich Korngold's dreadful melody and voices in German, a work I urge readers not to listen to, lest they curse me.

It is true that Freud wanted to establish his discipline within the canon of scientific thought and clothe it in objective explanations, drawing on categories he formulated without much data support, since he lacked access to electroencephalograms with the technological level we have today, nor case studies with well-organized data to arrange and access the areas of pleasure and negative experiences. He also rejected the physiology that social phenomena evoke in order to analyze them. But it would be extremely foolish to dismiss the insights of his thinking on what drives the individual, on the origin of pathological behaviors, because of this. Likewise, it would be completely unwise to dismiss Dostoevsky's work because of his gambling debts...

Freud is immersed in late 19th-century thought, but he did a good job of discerning behaviors that are part of human nature but are rejected by society due to taboos, idiosyncrasies, and repression. He also does justice to the scientific method by asserting the importance of analyzing each case individually before attempting to establish general rules for drawing conclusions about any given individual.

In this sense, seeking a greater understanding of human phenomena, delving into the foundations of the study of mass behavior, is essential to developing psychoanalysis. Freud criticizes Le Bon, and his comments seem valuable to me for understanding what we are experiencing in Brazil today.

Let us first examine the French thinker's thinking: for Le Bon, under certain conditions, "the individual begins to feel, think, and act very differently from what was expected when incorporated into a body of people that has acquired the quality of a 'psychological mass.'" The French scholar then seeks to identify the causes of this difference:

“The first is that the individual forming part of a crowd acquires, solely from numerical considerations, a sentiment of invincible power which allow him to yield the instincts which, had he been alone, he would per force have kept under restraint. He will be the less disposed to check himself from the consideration that, a crowd being anonymous, and in consequence irresponsible, the sentiment of responsibility which always controls individuals disappears entirely. (…) We had long contended that the core of what is called conscience is ‘social anxiety’. (…) The second cause, which is contagion, also intervenes (…). In a crowd every sentiment and act is contagious, and to such a degree that an individual readily sacrifices his personal interest to the collective interest. This is an aptitude very contrary to his nature, and of which a man is scarcely capable, except when he makes part of a crowd. (…) As a third cause, and by far the most important (…), [is] suggestibility. (…) having entirely lost his conscious personality, he obeys all the suggestions of the operator who has deprived him of it, and commits acts in utter contradiction with his character and habits. Under the influence of a suggestion, he will undertake the accomplishment of certain acts with irresistible impetuosity. This impetuosity is the more irresistible in the case of crowds than in that of the hypnotized subject, from the fact that, the suggestion being the same for all the individuals of the crowd, it gains in strength by reciprocity. (…) It instantly goes to extremes: in a suspicion, once voiced, turns immmediatly into ‘incontrovertible evidence’, a seed of antipathy becomes ‘furious hatred’. Itself tending to every extreme, the mass is also only excited by immoderate stimuli. Anyone seeking to move it needs no logical calibration in his arguments but must paint with the most powerful images, exaggerate, and say the same thing over and over again. Since the massa has no doubt about what is true or false and is at the same time aware of its immense strength, it is as intolerant as it is accepting authority. (…) What it expects in its heroes is brawn, even a tendency to violence. It wants to be dominated and suppressed and to fear its master. Basically conservative in all things, it has a deep aversion to all innovation and progress and an immeasurable reverence for tradition”.

(Le Bon, p. 10-13, apud Freud, op. cit. p. 24).

A feeling of invincibility, anonymity, irresponsibility, suggestibility, contagion, impetuosity, reciprocal stimuli, oscillation between extremes, aversion to authority, a taste for being manipulated by a leader, reverence for tradition: this results in a mass in which the individual, upon being incorporated, loses his or her conscious personality and becomes controlled by an "operator." This is a fairly perfect description of what we see in the political crowds that gathered during the pandemic, against the health measures imposed by the authorities.

The mass is impulsive and does nothing premeditated; the mass desires things passionately, but never for long; it is incapable of conceiving a long-term intention. It does not consider any delay between desire and the achievement of the desired thing. It has a sense of omnipotence; for the individual in the mass, the concept of impossibility ceases, and because of this, it is extraordinarily suggestible, credulous, and uncritical. The crowd thinks in images that evoke one another through association, just as they appear to the individual in states of fantasy, with no congruence with reality: the crowd, in other words, defends antagonistic ideas, "knows neither doubt nor uncertainty," and above all, cares nothing for truth: it cannot distinguish truth from its fantasies (Freud, Chapter II, Le Bon's Portrayal of the Mass Mind).

The Austrian physician and the distinguished Frenchman agree that reason and argument are useless in combating words and formulas repeated in the presence of crowds, which gain a primitive, "magical power" in a shared subjective reality where the life of imagination and illusion predominates. And finally, he highlights:

“The mass is a docile herd, never capable of living without a master. So powerful is its thirst to obey that, should anyone appoint himself its master, it will instinctively bow down to him. (…) The leader must nevertheless possess personal qualities that suit the mass. He must himself be in thrall to a powerful belief (in an idea) if he is to inspire belief in the mass”.

Le Bon derives the importance of leaders from the ideas they fanatically defend, Freud recalls. The mass operator is established through a bond of prestige. For Le Bon, prestige would be the type of dominance that an individual, a work, or an idea exerts over us (Freud, op. cit. p. 28). "Something that paralyzes our critical faculty and fills us with admiration and respect." For Freud, this would be equivalent to saying: fascination in a state of hypnosis. Hypnosis is a relationship of domination and control that is established, through several combined factors, between two people.

Despite recognizing it as a brilliant description, Freud makes some critical comments about Le Bon. He believes that nothing the French thinker said is exactly new, and to reach this conclusion, he refers to "various poets." The psychoanalyst asks: what is the element that holds these people together? He revolutionizes by saying that every institution is nothing more than a mass of people; just a more organized mass. In this context of dissatisfaction with Le Bon's theory, Freud adds other aspects that enrich the theory of mass behavior and the individual. One of these aspects is libido.

But let’s have it clear: in Freud’s language, libido does not necessarily relate to sexual drive. Libido charges have more to do with emotive impact and connection, a reasoning that is based on physical sensations and reactions, rarely rational. To fully understand this one must surely have dived in the mass mind, clearly, and we keep thinking of the connection between Freud and the reader, the one who has rescued him back from it.

No doubt, however, that participating in the masses also offers plausible circumstances in which the sexual drive can find expression, with the advantage of releasing constraints, although all this may happen in the uncouncious level. Another aspect Freud raises is the phenomenon of identification. One person can identify with another, due to the injustice done to them, or with several people, around a dissatisfaction. In Freud's view, these elements precisely provide the "connection" between people within a mass.

To Freud's comments, I would add two observations. What Freud fails to explain, first, is the question of the individual's strength. If an individual's power to restrain himself is less than the compelling and attractive force emanating from the mass will (i.e., the general will, as in the French Revolution), why do some individuals occasionally resist the pull of the masses, retaining the common sense that there is no such thing as invincibility, respect for authority, or the benefit of the doubt? Neither Le Bon nor Freud analyze how one might explain, then, individuals speaking out or exhorting against a mass of people urging in protest.

But in a letter to his fiancée Martha Bernays in 1883, psychoanalyst Jacqueline Rose tells us that Freud writes: "The people judge, think, hope, and work in a manner profoundly different from ours." They do not consider themselves part of the people. How, then, could Freud have escaped this logic of the people, the expression he uses to express the meaning of "mass"? In a letter to his sister in 1881, he describes the crowds he saw being organized in his time as "a different kind," "sinister," which "knew neither fear nor shame." It was collective hatred that was being raised against the Jews; and Freud was one of them.

It would seem, then, that only another mass, or belonging to a distinct crowd, albeit organized in institutions, would be able to resist the call of another. Since Freud was part of another mass, that of Judaism, he rejected the Nazi-like masses that organized under the national banner of his country, claiming to be "the people." Or perhaps the fact that Freud was part of his own institution, Medicine, or of a study group he established in a new discipline, could be a possible answer to this question.

Indeed, generally speaking, what we are seeing in our current reality is this: one is either for or against, and those who do not want to be reduced to one mass or the other are punished with some resource held by them, or excluded from the groups that form within these masses. Religions themselves harbor, often without objection, initiatives that appeal to a general will of the people, to a mass. In the Catholic Church, it is called "sensus fidei."

Freud delves into the particularities of an institution by considering them as a type of organized multitude. He analyzes the Church and the Army, which will be the subject of my attention in a future text. In your text, I missed the distinction between different types of crowds. I think it's necessary to distinguish between multitude, mass (a crowd organized by a leader), ochlos (the mob), and people (a population endowed with culture, with its own collective identity), which neither Freud nor Le Bon do.

But a second aspect that Freud and Le Bon perhaps missed was remembering the power of the call from urgency. The emergency aspect gives priority to the general will over the will of the individual, the feeling of Armageddon. The threat to survival, the danger to collective life, the destruction of values, is generally urgent and immediate. Panic and fear are also indispensable factors in justifying the self-abdication that leads to the formation of masses, and it seems to me that their operators pay very careful attention to exploring these elements, constructing scenarios that go beyond a merely dogmatic proposal.

The psychoanalyst continues, however. He also analyzes hypnosis and love, without distinguishing love from passion. For him, hypnosis is essentially a "mass of two." He asserts that the connection between love and hypnosis is very close, with obvious correspondences. He describes love as a phenomenon in which an individual begins to idealize and attribute sublime characteristics to the loved one, or even characteristics that they lack; in such a way that the loved one hijacks the ego, and the loved one begins to be placed in the place of their own self, above their own needs, above self-love. "Only love has had an effect as a civilizing factor in the sense of a turning away from egoism towards altruism." Hypnosis is a step further: a process in which the person, completely emptied of themselves, begins to act according to the suggestions of another, without being aware of this process, in a sequence of compulsive acts. If the reified person resists, Freud does not address this issue, although experience has also proven that hypnosis has side effects on the person who is objectified, both in the short and long term.

The founder of psychoanalysis also asserts that it would be necessary to further study how the reduction of narcissism can be generated by the libidinal bond with other people in the mass movement. He states that "self-love only comes up against the love of others, the love of objects" (Freud, Op. cit. Chap. VI, Other Tasks and Areas for Study, p. 54). From the analysis of the relationship between two people, he derives a "formula for the libidinal constitution of the mass" (cf. diagram in Chap. VIII, Being in Love and Hypnosis). To reach this conclusion, he reasons as follows:

“The question will immediately be asked whether community of interests alone, without any libidinal contribution, will not in itself inevitably lead to toleration of and consideration for the other. (….) But the fact is, experience has shown that, as a rule, where there is co-operation, libidinal bonds are produced between comrades that extend the relationship between them beyond what is advantageous and pin it there. (…) Now, our interest is going to be very much in knowing what kinds of tie those are within the mass. Up to now, our psychoanalytical theory of neurosis has concerned itself almost exclusively with the attachment of such love drives to their objects as still pursue direct sexual goals. Clearly, in the mass, no such sexual goals can be at issue. we are dealing here with love drives that, without being any less vigourous in their effect, have nevertheless been deflected from their original goals (…)”. (Freud, Op. cit. Cap. VI, Other tasks and areas for Study, p. 54)

In short, this seems important because, by analyzing the different degrees of love/passion, he considers that this phenomenon can be transferred to the bonds that individuals establish with each other when they become part of a mass of people.

I reflect that much of this study is present in society today and has evolved with the scientific progress of neurological and behavioral studies, in experiments and more specific analyses. Ethology, psychoanalytic, and social theory have developed significantly since then to analyze this phenomenon. This is the case, for example, with the literature on Echo Chamber, or the broken windows theory, or the apocalypse of Calhoun's Utopia. However, considering the number of people who gather in masses today, we know that this is not necessarily consolidated knowledge to prevent violent or degenerative behavior among masses in society. Now, the difficulty in undoing or controlling mass behavior during the pandemic completely ignored all these characteristics that Le Bon and Freud demonstrated in practice, due to the ineffectiveness of insisting on rational arguments, the preponderance of authority, the application of penalties, etc. We saw that the increased application of penalties fueled the virulence of a discourse and the resulting violence; worse still, it transformed the mass phenomenon into an event of abolition of the legal order, of liberation against an oppressive authority. A campaign aimed at minimal effectiveness should have offered a solution that included this dimension of affects and a satisfactory channel for converting the sexual impulse repressed during the period of social isolation, which, in the view of experts, is the cause of the formation of the masses. The result, we see, is that all the repressed sexual impulses of individuals have become a substrate easily manipulated through leadership, converted into love for comrades and love for a leader—a leader with whom an identification was established, and who fulfilled all the requirements to excite the masses' sense of invincibility and fantasy.

Now, the difficulty in undoing or controlling mass behavior during the pandemic completely ignored all these characteristics that Le Bon and Freud demonstrated in practice, due to the ineffectiveness of insisting on rational arguments, the preponderance of authority, the application of penalties, etc. We saw that the increased application of penalties fueled the virulence of a discourse and the resulting violence; worse still, it transformed the mass phenomenon into an event of abolition of the legal order, of liberation against an oppressive authority. A campaign aimed at minimal effectiveness should have offered a solution that included this dimension of affects and a satisfactory channel for converting the sexual impulse repressed during the period of social isolation, which, in the view of experts, is the cause of the formation of the masses. The result, we see, is that all of the repressed sexual drive of individuals has become a substrate easily manipulated through leadership, converted into love for comrades and love for a leader—a leader with whom an identification has been established, and who fulfills all the requirements to excite the masses' sense of invincibility and fantasy.

We have not yet found a solution, and so we see that politics in many places has become a competition between these leaders' domains of influence over highly susceptible masses.

Political scientists more briefly call this phenomenon "populism." But there are many processes established through causal relationships and specific events, many of them hidden, which recur within this category so widely propagated in public debate. Ignoring how populism works in practice ends up perpetuating the problem of movements that undermine the social, economic, and political order. How can we reduce suggestibility and susceptibility? This would involve a policy of strengthening the personality of each individual, and from this we see the impasse, since every government typically develops public policies for the masses.

On the contrary, if we observe more closely how politics has been organized in democracies, we can see, as I wrote at the beginning, that the democratic political system has come to praise and value leaders and political parties capable of mobilizing and continually nurturing large masses, as a sign of success, of electoral success. What matters is the number of followers and the readiness with which they respond to their leader's call.

The people are a source of legitimacy, of course: it's stated in our Constitution. But are the people a mass? The mass is, by the consensus definition of many experts, a group of individuals who have abdicated their own conscience, linked by impulses that go beyond the objectivity of a common interest, or the legitimacy of a cause, manipulated by an operator with whom they have developed an affective relationship, channeled by libido.

Another flaw of ours is projecting onto this mass phenomenon a thought and judgment that doesn't necessarily emanate from the masses. The ongoing case regarding an attempted coup d'état, as stated in the Prosecutor General's Office complaint, categorically states that the objective of an alleged criminal group—composed of individuals with very different profiles and motivations—was to remain in office, and that to achieve this, they allegedly resorted to a campaign to delegitimize the electoral process.

However, we see that studies on the masses agree that every mass formation is predicated on the excitement of violence, virulence, the gathering of a sufficient number of people to produce anonymity, a dynamic that demands a call against authorities... It is clear that the objective of questioning a given process could be replaced by any other issue at the center of public commotion, as we have seen. The masses and their leader are primarily interested in exercising a sense of invincibility: the passion for their comrades and the act of destroying an antagonist. It seems to be all about exercising the joy of leading crowds to fuel narcissism and increase prestige. The antagonist, all the better, is hand-picked: someone who cannot enter the political sphere where the clashes occur, people who must confine themselves to their contrite domain. Once they exceed their own domain, they become vulnerable.

The goal of remaining the leader of a mass requires, as Freud and Le Bon elucidated, that the leader demonstrate certain characteristics of aggressiveness and virility demanded by the masses. Remaining in office or not could be useful, but relevant for the greatest instruments to continue exerting fascination over the crowd; just as imprisonment and humiliation could be as useful, if not more so. The pretexts for satisfying libido in a crowd, directing one's impulses toward one's comrades, in a reasonably anonymous manner, without the constraints and burdens that social life imposes, could be numerous, and we have indeed seen that they fluctuate rapidly. These are all very different things, demanding from the masses a degree of absolute adherence, requiring no arguments, reasoning, or in-depth reflection.

In those decades of the early 20th century, Le Bon and Freud, as well as operas, Chaplin's cinema, redeeming the figure of the dictator, and so many other intellectuals, realized this. They turned to trying to raise awareness among the people and public opinion about this impoverishing aspect of the masses. They believed in and defended love and fraternity as a civilizing idea, rather than an individual experience. At least we know that this emancipatory appeal using mass media was not enough to overcome the problem. We also know that rational and logical arguments, or the defense of the legitimacy of institutions, also failed, because that is precisely what these masses are moving against. Since these responses were insufficient, the only option left was confrontation; and having chosen confrontation, the path to conflict was paved. Appeasement was a mistake; but confrontation also failed to offer a response compatible with the public good; it led to war. Since we still do not have the answer to how to satisfy these masses of what they lack, we continue to observe the deterioration of peace. But we should at least observe what did not work in the past, nor could work, so as not to spread the problem or waste our time.

* Political scientist, poet and diplomat. www.anapaulaarendt.com .

Comentários